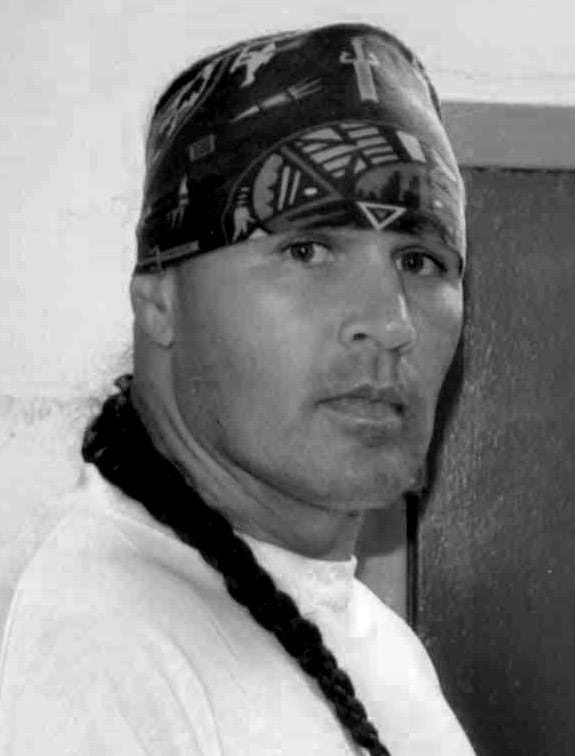

A Monroe County grand jury has declined to indict a controversial parolee who was facing felony charges for registering to vote illegally that could have sent him back to prison.

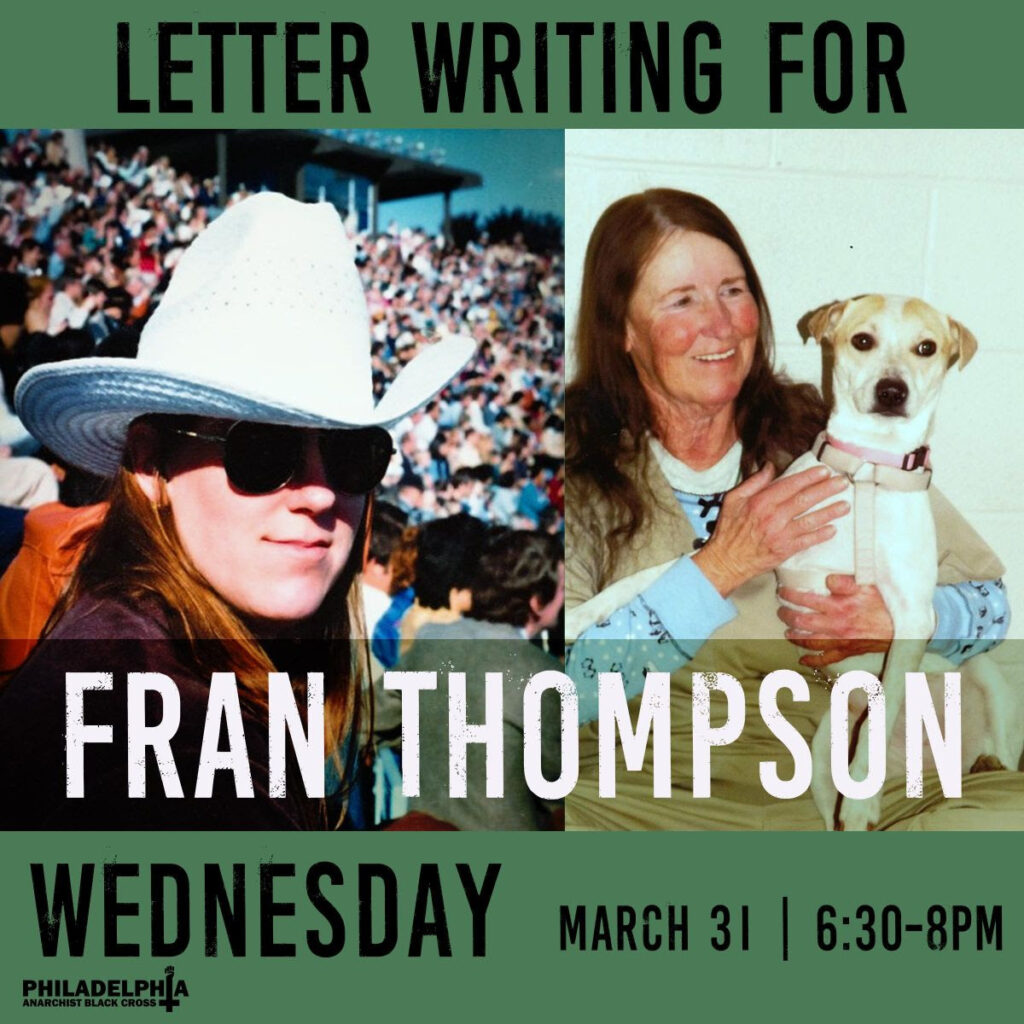

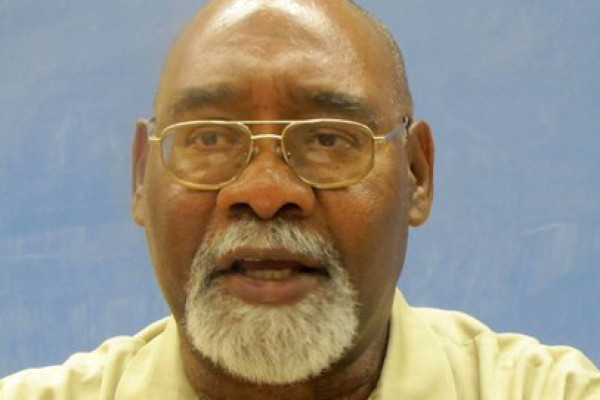

The parolee, Jalil Muntaqim, was imprisoned under his given name, Anthony Bottom, for nearly 50 years for his role in the murder of two New York City police officers in 1971 before his release in October.

The Monroe County Public Defender’s Office confirmed Tuesday that the grand jury last week “no-billed” Muntaqim’s case, meaning the jury declined to indict. The case is now sealed.

“I think a no-bill was the right outcome in this case,” said his public defender, Jaquelyn Grippe. “Mr. Muntaqim is a truly inspirational person and I can say that it was my privilege to get to know him through this process.”

Originally from San Francisco, Muntaqim, 69, settled in Brighton with a friend upon his release.

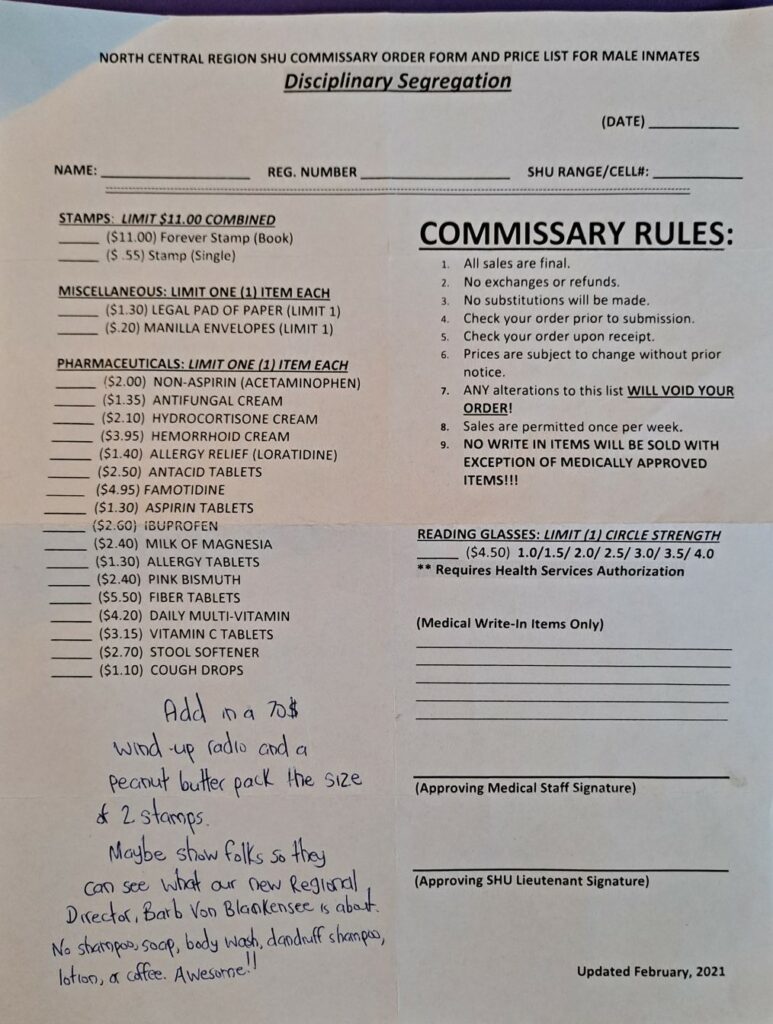

A day after being set free, however, Muntaqim filled out paperwork given to him by the county Department of Human Services, which helps former prisoner’s acclimate to civilian life. The packet included a voter registration form, despite Muntaqim not being eligible to vote.

Prosecutors alleged that when Muntaqim filed his voter registration form with the county Board of Elections, he committed two felonies — tampering with public records and offering a false instrument for filing. He was also charged with providing a false affidavit, a misdemeanor.

The Board of Elections subsequently rejected his registration, and the former chair of the county Republican party, William Napier, seized on the matter as a question of voter fraud.

District Attorney Sandra Doorley has said that the charges against Muntaqim were about answering allegations of voter fraud in the weeks before the election and that the case seemed straightforward.

“Is it a major thing?” she asked of the charges. “No.”

If convicted on the charges, Muntaqim’s parole status would have required him to return to prison.Billie Bottom Brown, 85, the mother of Jalil Abdul Muntaqim, aka Anthony Bottom, speaks outside of Spiritus Christi Church on behalf of her son on Nov. 12, 2020.CREDIT DAVID ANDREATTA / CITY

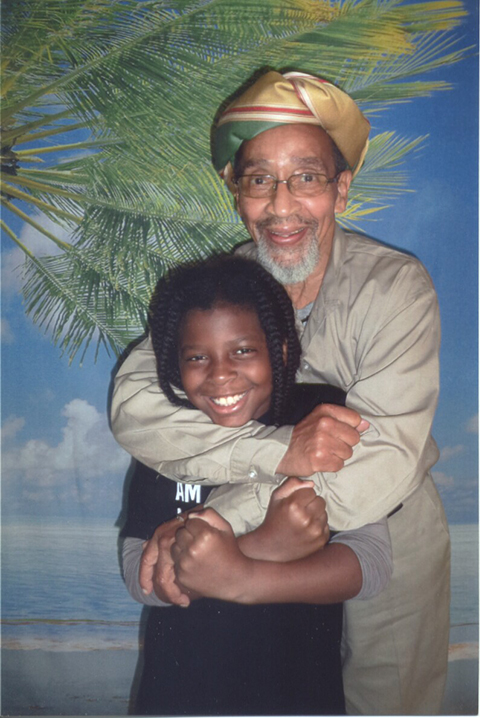

Muntaqim enjoyed much public support from family, friends, and Rochester’s activist community, who echoed the argument of his public defender that Muntaqim did not realize he was not eligible to vote.

Parolees are not allowed to vote in New York upon release from prison without receiving a conditional pardon to restoring voting rights from the governor.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has issued such pardons as a matter of course on a monthly basis since 2018, when he signed an executive order directing the corrections commissioner to submit to him each month a list of every felon newly eligible for parole, with each name to be “given consideration for a conditional pardon that will restore voting rights.”

Most parolees receive their pardon, which does not expunge their criminal record, within four to six weeks of their release. Cuomo denied Muntaqim a voting pardon in November, however, after news reports of Muntaqim’s predicament.

A national movement to restore voting rights to formerly incarcerated people is gaining steam, and Muntaqim’s case became a rallying cry for advocates.A supporter of Jalil Muntaqim holds aloft a sign at a rally calling for authorities to drop the voter fraud charges against him. Nov. 12, 2020.CREDIT DAVID ANDREATTA / CITY

“I certainly hope that legislation is passed in the future that expands on Gov. Cuomo’s executive order allowing parolees the basic right to vote,” Grippe said.

Twenty states allow parolees to to vote upon their release, according to the Sentencing Project, an advocacy group for criminal justice reform.

The concept of disenfranchising felons dates to colonial days, when certain criminals were striped of rights in a practice known as “civil death.” Later Americans applied a racist twist to the practice after the Civil War, when many states used it to deprive Black men of the vote they had recently gained.

Today, the impact of these laws still falls disproportionately on poor people of color.

The Supreme Court interprets the Constitution in such a way that upholds these restrictions.

David Andreatta is CITY’s editor. He can be reached at [email protected].ShareTweetEmail