Eric King’s civil rights lawsuit alleges a pattern of abuse by Bureau of Prison guards across several facilities.

by Natasha Lennard, The Intercept, May 28, 2021

The Federal Correctional Institution, Englewood on Feb. 18, 2020, in Littleton, Colo.

Photo: Vic Moss/Getty Images

One morning in early 2018, Eric King was awoken at 5 a.m. and taken out of his solitary confinement cell by prison guards at the federal United States Penitentiary, McCreary, in Kentucky. King didn’t know the correctional officers by name, having been recently transferred to the facility for unexplained reasons.

That morning, the guards had something to tell King, according to a civil rights lawsuit filed this week on his behalf against the federal Bureau of Prisons and over 40 of its correctional officers. Members of a national white supremacist gang active in the prison had, the guards allegedly said, made threats on his life.

King is a known anti-fascist activist and anarchist. He is serving a 10-year federal sentence for throwing Molotov cocktails at an empty government office in Kansas City, Missouri, in 2014. He said throwing the Molotov cocktails, which he did not light, was in solidarity with the Ferguson rebellion that year, part of the Black liberation struggle against police violence.

That day in 2018, in prison in Kentucky, the guards warned King that the white supremacists wanted to gravely harm him. They asked him if he felt safe. King chose the answer that he believed would come with fewest repercussions. “Yes, I feel safe,” he said, according to the lawsuit.

“At that point,” the lawsuit claims, the correctional officers told King “he could leave, but directed him to exit through a different door than the one through which he entered.” King walked through the door. “[H]e realized that, rather than being in a hallway or a public space on his way back to his cell, he had entered into an enclosed, locked outdoor area. Inside this room was a prisoner known to be a member of the aforementioned gang.”

The white supremacist — who dwarfed the 5-foot-7, slightly built King — attacked the anti-fascist. The guards did nothing to intervene. King had, he felt, been trapped by correctional officers colluding with white supremacist gang members. Following the reported assault, King received a disciplinary citation for fighting.

King claims the incident was a part of an ongoing pattern of harassment and violence that he has endured in recent years at the hands of the Bureau of Prisons. The Civil Liberties Defense Center, a legal nonprofit organization, filed the civil suit on his behalf, alleging that his “constitutional rights have been continually violated since 2018 in retaliation for his political and anti-racist actions while incarcerated.”Join Our NewsletterOriginal reporting. Fearless journalism. Delivered to you.I’m in

The Bureau of Prisons responded to questions relating to the case by stating that it does “not comment on pending litigation or matters that are the subject of legal proceedings.” An agency representative added that “it is the mission of the Bureau of Prisons to operate facilities that are safe, secure, and humane. The BOP takes seriously our duty to protect the individuals entrusted in our custody, as well as maintain the safety of correctional staff and the community.”

King has been held at Federal Correctional Institution, Englewood in solitary confinement, known officially as a Special Housing Unit, for over 1,000 days. He is currently one of only 80 people in the federal system who have been held in the unit for more than a year.

His attorneys say in the suit that he has faced no less than “torture” — including at one point being shackled, “naked and exposed,” in four-point restraints for over eight hours. On another occasion, King claims a guard beat his feet with a metal detector wand as he stood in his underwear in the shower; the lawsuit claims that King was knocked to the ground, left with a concussion and in need of six stitches.

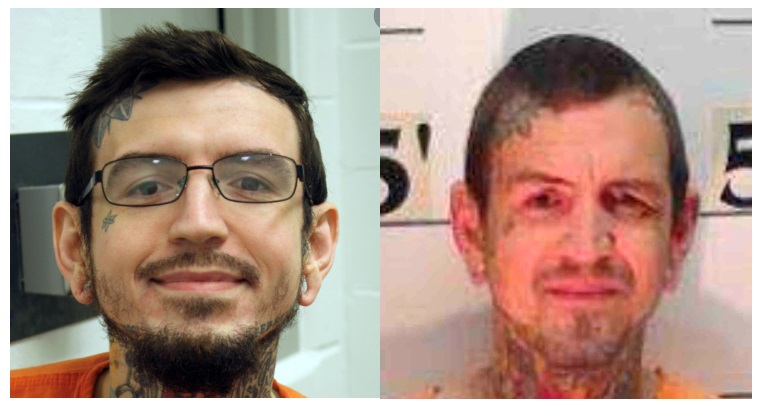

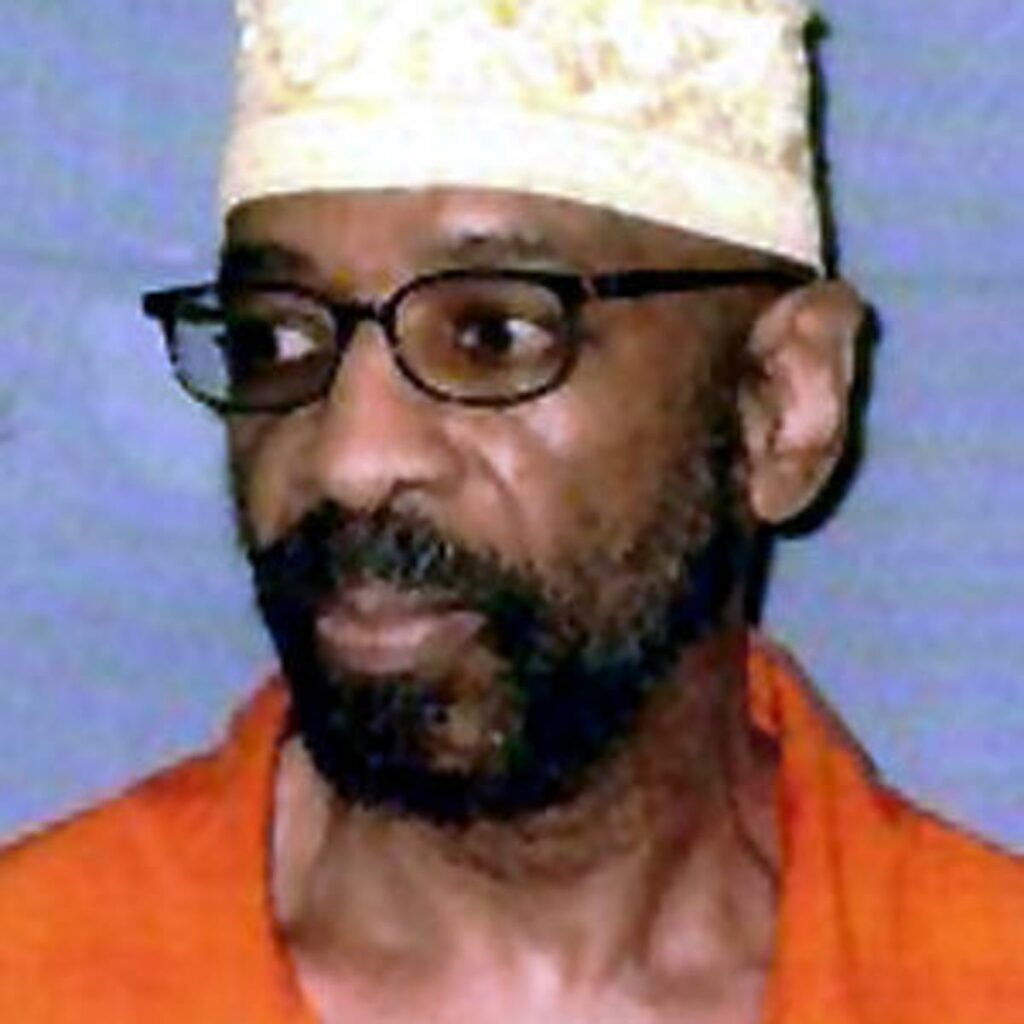

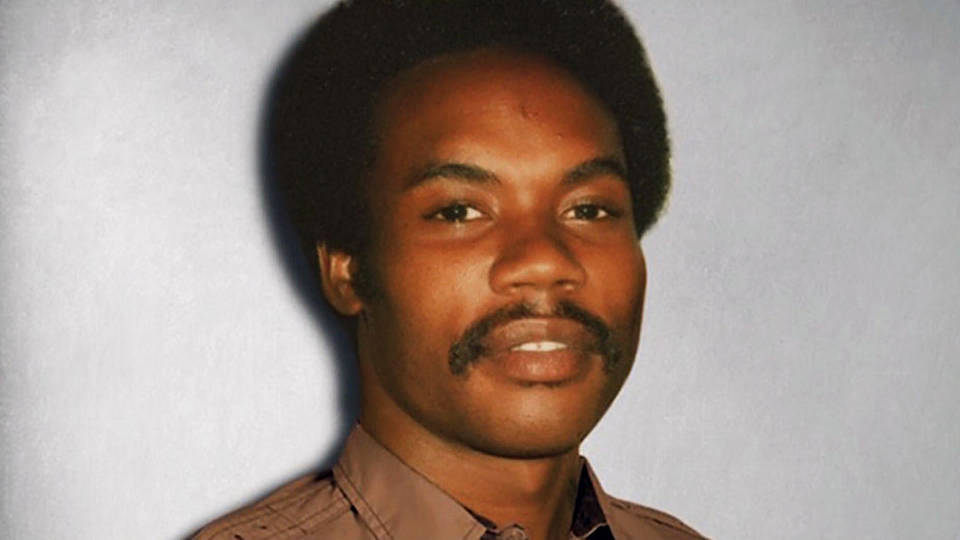

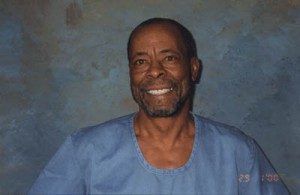

Eric King is shown in 2016 at the Leavenworth Detention Center, a privately run maximum-security prison in Leavenworth, Kansas, operated by the firm CoreCivic.

Photo: Courtesy of Eric King Support Committee

Following almost every incident of violence alleged by King, guards have issued disciplinary complaints against him. He now faces a further 20 years in prison for allegedly assaulting a federal officer; he claims he was trying to defend himself as he was beaten by guards in a small storage area beyond the view of prison cameras.

The incidents alleged in the lawsuit span numerous federal facilities and involve dozens of officers. As such, the case resists the usual pro-law enforcement talking point about “bad apples.” Taken together, the accusations read as an indictment of the entire federal prison system.

“Eric King has faced chronic, targeted harassment, as well as severe emotional and physical torture, from BOP officers and known white supremacists working together, for over two years while held in solitary confinement,” Lauren Regan, one of King’s attorneys with the Civil Liberties Defense Center, said in a statement. “We reasonably believe this treatment has been in retaliation for his political views and First Amendment-protected activity.”

A WHITE MAN in his mid-30s, King appears to embody the figure of anarchist agitator so maligned by politicians across the political spectrum during last summer’s Black-led anti-racist uprisings. Though he was convicted of attempted arson, King committed minor property destruction, specifically targeting a congressional office that he knew to be empty at the time. No one was hurt.

Facing hefty federal charges, he took a plea deal to serve 10 years. At his sentencing hearing, he made clear the motivation for his actions. “The government in this country is disgusting,” he said. “The way they treat poor people, the way they treat brown people, the way they treat everyone that’s not in the class of white and male is disgusting, patriarchal, filthy, and racist.”

Following the George Floyd rebellions, hundreds of anti-racist, anti-fascist protesters now find themselves in a similar position to King: facing highly politicized, overreaching federal charges and potentially long sentences in federal facilities, where white supremacist violence is known to flourish. Over 300 federal indictments were handed down across the country from late May to late September 2020, compared to an average of 10 such indictments in the summer period in years prior.“I’ve been treated deplorably. For the last two years I’ve been stuck in a 6′ x 9′ cage, denied access to my family and my lawyers, and subjected to physical and emotional torture.”

King’s allegations of consistent, targeted harassment by guards and white supremacist gangs paint a chilling picture of the brutality these anti-fascists — many of whom are not white — could face.

“I’m a human being with a family. I’ve been treated deplorably. For the last two years I’ve been stuck in a 6′ x 9′ cage, denied access to my family and my lawyers, and subjected to physical and emotional torture,” said King in a statement. “They’ve done this because of my beliefs, not because of my actions.”

In 2019, a report by the House Subcommittee on National Security found the federal prison system to be a hotbed of misconduct, sexual assault, and other violence — committed by correctional officers both against incarcerated people and female prison staff members. The report also pointed to the way officers permit certain incarcerated people to carry out assaults too. “Misconduct in the federal prison system is widespread, tolerated and routinely covered up or ignored, including among senior officials,” the New York Times reported, citing the congressional investigation.

The civil rights lawyers who filed King’s federal suit only learned the extent of their client’s suffering while building his defense for the hefty criminal charges he faces for allegedly assaulting an officer. Regan, one of the attorneys, described violence in the federal prison system as “like a mold, which grows rampant when unchecked in a dark place.”

Any litigation in which an incarcerated person is making claims against law enforcement officers faces an uphill battle: King’s word against that of officers with badges. Yet the lawsuit, Regan hopes, will go some way to keep in check Bureau of Prisons correctional officers’ seemingly retaliatory violence against King. “We feel it is the right thing to do, whether we win or not, to shed light on this injustice,” Regan told me. “We know there are hundreds of thousands of other cases similar or even worse than this one throughout the criminal punishment system.”

Regan is under no illusions about the difficulty of winning a case alleging widespread, state-sanctioned brutality. Even if a federal judge were to rule in King’s favor, no given legal victory can constitute justice within the inherent violence of the carceral system. For King’s attorneys, his case is nonetheless an opportunity to expose institutional violence and white supremacist collusion. And beyond this broader moral imperative, there is a deep concern for King’s life. The correctional officers “seem intent on killing him or allowing other people to kill him,” Regan told me. “We want to keep him alive until his release.”